Reforming the Green Belt under Labour – Implications for Summix

Summix, like many Strategic Land Promoters, has been avidly following the plethora of announcements Labour have been making over the past couple of weeks including the Chancellor’s maiden speech, the King’s Speech and last week’s Deputy Prime Ministers address to the the House of Commons. What is consistently recurring is that Labour are clear that Local Authorities will have a choice about how they deliver the numbers (1.5 million homes), not whether they deliver them. Potential mechanisms for delivery include “new towns” and urban extensions and reforming the Green Belt. It is the latter that this article will cover.

Many strategic sites in the existing defined Green Belt are taking a long while to promote or have stalled as building on the Green Belt is politically controversial at a local level and the process for removing sites from the Green Belt is long term, requires a very strong case to justify any alteration and consequently requires very patient capital.

A simple scroll of the planning and mainstream press in recent weeks shows that Green Belt is a current hot topic as part of the reforms being progressed. The new Government has an excellent opportunity to redefine this often misunderstood and politically controversial area of planning policy.

There is no denying that it is a dated policy concept that was conceived a long time ago. The world is a very different place now, and it feels timely to consider reviewing whether it’s fit for purpose in the modern world. It feels highly likely given the amount of debate occurring that it is outdated and needs reform. The policy needs to consider implementing a more appropriate and modern definition to make it capable of being better understood by all parties. A refresh of the Policy has the potential to bring greater speed and consistency to decision making in Green Belt areas whether that is applications or Local Plan related changes to the old boundaries.

Of note, is a recent and thought-provoking article by Martina Lees in The Sunday Times. This secures the views of several industry leading experts including Zack Simons, a Barrister at Landmark Chambers who specialises in Green Belt law.

Simons in the article calls the Green Belt “the most familiar and least understood plank of England’s planning policy … The confusion starts with the name. It’s not all green and it definitely isn’t a belt.” The Green Belt is a planning designation that does not necessarily reflect the green or ecological value of the land and swathes of it consist of derelict sites.

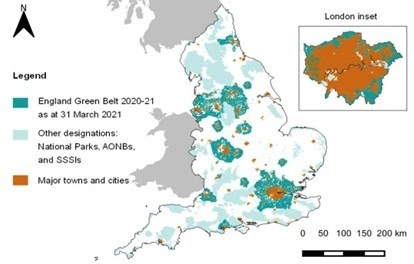

Figure 1. Green Belt in the England

Simons further states: “There’s widespread misunderstanding of what the Green Belt is, and a political unwillingness to consider whether the policies related to it remain fit for purpose. We need to find an appropriate balance between the importance of meeting housing and economic needs and protecting land that genuinely needs to be kept open. An independent and objective review of the purposes of and policy for the Green Belt should be undertaken that understands and reflects that balance. Green belts have nothing to do with preserving scenic beauty or landscape quality. We have national parks and areas of outstanding natural beauty for that. They aren’t about protecting wildlife or precious habitats. They’re for something much simpler: keeping land permanently open and stopping so-called urban sprawl — a difficult term, when one person’s sprawl is another person’s home.” If green belt areas were called “urban containment zones” or something similarly unpoetic, more of us may understand what they are for”.

Labour has consistently stated the intention to progress the introduction of a new category of Green Belt being referred to as “Grey Belt” which would be the areas of existing Green Belt that are "poor quality and ugly areas". This Grey Belt could include uses such as disused car parks and wasteland. Labour wants Grey Belt land to be used for new homes, with half of all housing to be affordable housing.

Simons fears that focusing on the “greyness” of grey belt “risks perpetuating the error”. Talking of “poor quality and ugly” areas of green belt, as Labour has done, “completely misses what the Green Belt is about, which has nothing to do with beauty or ugliness. As the Grey Belt will be a new category, there is no official definition yet or data on how much of it exists. Exactly how many homes could be built on Grey Belt land depends on what its official definition will be.

But why is changing Green Belt policy important? The answer partly lies in the age of Green Belt policy and the limitations it represents. Since 1955 National Planning Policy has only allowed building in the Green Belt in “very special circumstances”. “That is a high policy bar,” Simons says. It stacks the scale against development by forcing decision makers to give “substantial” weight to any Green Belt harm. It can only tip in favour of approval if the benefits of a scheme are so significant that it “clearly” outweighs all its harms.

This month Angela Rayner, the Deputy Prime Minister and Housing Secretary, has stated an intention to publish a new National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) for consultation. She will also write to Councils to tell them to review their Green Belt boundaries and to earmark brownfield and Grey Belt land in them for development which represents a long overdue opportunity to re-define this area of planning policy as part of the wider strategy to accelerate housing growth.

Whilst this intention appears laudable, Green Belt reviews do take considerable periods of time to prepare and execute. Currently reviews can only be done as part of a formal review of the Development Plan. Whether some form of more flexible or less time-consuming approach will be in the NPPF consultation remains to be seen but is unlikely. If the review is via Local Plan review, there needs to be sound evidence underpinning any changes. This needs to be compiled appropriately and tested robustly to avoid or survive legal challenge.

Under the NPPF, all Local Planning Authorities (LPA) are required to prepare a long-term Local Plan, which sets out their local housing need and policies. But only 90 of England’s 309 Local Planning Authorities have adopted a Local Plan within the last five years (up to March 2024). In a world where Local Plans are often collaborative efforts involving multiple authorities; or are trying to meet the housing needs of adjoining authorities (e.g. Birmingham or Oxford where Summix are grappling with this issue), progressing the duty to cooperate, negotiating service agreements between plan making authorities, agreeing joint finance, recruiting experienced staff and achieving political cohesiveness is not the work of moments. It remains to be seen how this will be addressed and funded moving forwards.

As hinted at earlier in the article, Grey Belt as a new concept requires a clear definition and needs to be distinct from brownfield land as the NPPF already allows Green Belt development albeit with a very high policy bar. Additionally, the amount of land available requires accurate establishment. This point is well made by Sam Stafford (Planning Director of the Home Builders Federation) in the same Times article. There is “simply not enough” brownfield in the green belt to meet affected areas’ housing needs.

If the primary objective of the Labour reforms is accelerating housing delivery in the short-term, there is a risk in relying too heavily on previously developed land in the absence of significant Government funding. This is simply because there is difficulty in the private sector securing finance for these sites as these sites are often perceived as risky investments given the time they take to unlock against usual fund life spans. Additionally, the more complicated the site, the higher the capital cost of actually preparing a suitable pre-application submission, planning application (often accompanied by a comprehensive EIA/ES), and then delivering on sites which may be contaminated or require significance clearance as two common abnormal costs. Many of the Summix larger sites (both New Settlements and SUEs) on greenfield land where there are no abnormal delivery costs are having to work very hard to find viable solutions to achieve the policy expectations. On previously developed sites this process will undoubtedly be slower and more costly in most instances and the realistic solution is Government funding being needed. However, this is something to date where the details have not been communicated by Labour in any great detail, but presumably will be via Homes England.

This viability conundrum was well articulated by Knight Frank’s Charlie Dugdale on 9th July in his article titled “The Grey Belt has “Golden Rules”, but where’s the gold?” Dugdale correctly explains that land for development needs to be commercially viable. It needs to offer land promoters a return on their risk capital, whilst providing adequate security to raise finance for up-front infrastructure. If the land is urban infill, there will likely be alternative uses that have a higher value than residential development land (with 50% affordable housing). If the land requires enabling infrastructure (as many Grey Belt sites will) the associated costs will undermine viability. This is where Dugdale sees the real mismatch in expectations which the sector is still grappling with and awaiting further details from Labour.

A preferable reform of Green Belt policy to Grey Belt from a Summix perspective would be to focus on those Green Belt sites which are genuinely sustainable and linked to a strong evidence base background which do not conflict with the five long established purposes of the Green Belt. These are outlined by para 143 of the NPPF: a) to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas; b) to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another; c) to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment; d) to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns; and e) to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

There is a provision in the current guidance when drawing up or reviewing Green Belt boundaries local planning authorities should take account of the need to promote sustainable patterns of development (Para 147 of the NPPF). However, many authorities are unwilling to really challenge the Green Belt designations once established. Delivering sustainable patterns of development would benefit from greater prominence and weight in the Green Belt reform.

Across the Country there are many sites that are really sensible development locations and have in the recent past been low scoring sites in Green Belt Reviews when assessed against the purposes of Green Belt. Many are genuinely sustainable development locations such as being well located to existing employment locations, social infrastructure and public transportation but would not be covered by the emerging Grey Belt definition that is currently being promoted by Labour as they are greenfield and are not previously developed or in any way ugly (as subjective as this judgement is). It is considered likely that should a more positively weighted policy be directed towards delivering sustainable patterns of development, these sites would come forward despite not being Grey Belt in character.

If Green Belt Policy were to be re-focussed not only on freeing up the Grey Belt but also added increased weight to the consideration of achieving sustainable patterns of development where the five purposes of the Green Belt are not adversely impacted, it would be a positive step towards freeing up housing sites where they are in demand and can deliver truly sustainable development.

Green Belt boundaries are intended to be longer term policies than the Development Plan (i.e. more than the standard 15 years) but they were never intended to operate in perpetuity and should be subjected to periodic review. There needs to be an appropriate evidence base and regular process of review to make Green Belt policy more contemporary, it should go further than just adding a further typology in the form of Grey Belt and should delve deeper to consider whether the designations remain fit for purpose. The Labour administration acknowledges this, and the time feels appropriate for the planning industry and local politicians to try find an appropriate balance between the importance of meeting housing, economic, leisure and recreational, agricultural and biodiversity needs and protecting land that genuinely needs to be kept open for the purposes of Green Belt.

In summary, Labour has an opportunity to be strong and add certainty to this long standing and often misunderstood area of planning policy. It is timely whilst the housing crisis and the wider topic of planning reform is high on the political agenda, and they have a secure majority in the Commons to push through appropriate reform where it is justified. Finding a pragmatic solution to Green Belt remains critical to trying to solve part of the housing crisis along with the other measures they are implementing including New Towns.

The Labour Government has promised to apply a common-sense approach to the Green Belt, asking local authorities to regularly review boundaries. My fear as a planning professional is tinkering around the edges of the Green Belt policy and asking for unrealistic regular reviews without adequate funding or resources for authorities to formulate a robust evidence base will not yield any delivery quickly. This will not unlock the many needed sites in the places they are actually needed in a sustainable and viable manner. Additionally, any form of subjective definition on matters such as considering ugliness is not going to speed up delivery and will simply lead to protracted debate and disagreement between those seeking to promote land, residents and local authorities.

Peter Bateman - Planning Director Summix July 2024